While AJF is not multilingual, our readership certainly is, and we often hear how unfortunate it is that our articles are not translated into other languages. We cannot afford to do that—but what we can do, when a piece is supplied to us in its English translation, is publish it in the original language as well.

We are extremely happy for the opportunity to reproduce the following interview of Italian master GianCarlo Montebello in both English and Italian. I would like to thank Eliana Negroni for her tireless efforts to bring this long project to the finishing line. (Please scroll down for the Italian version.)

—Benjamin Lignel, editor

“What is simplicity? A non-manifest complexity.”

—GianCarlo Montebello

GianCarlo Montebello is one of a handful of goldsmiths around the world who is respected both for his own design work and for the design development and manufacturing work he did for famous others. In 1967, he founded the company GEM, which oversaw the production of limited-edition jewelry by fine artists: César, Sonia Delaunay, Piero Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hans Richter, Larry Rivers, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jesús Soto, and Alex Katz are some of the personalities with whom he worked. In 1978, Montebello began designing work under his own name and took part in the establishment of the jewelry department of the Istituto Europeo di Design (IED, European Institute of Design) in Milan. Since then he has set up collaborations with a number of artists, galleries, and collectors, especially in France, the United States, and Japan, and has been featured in countless exhibitions worldwide.[1]

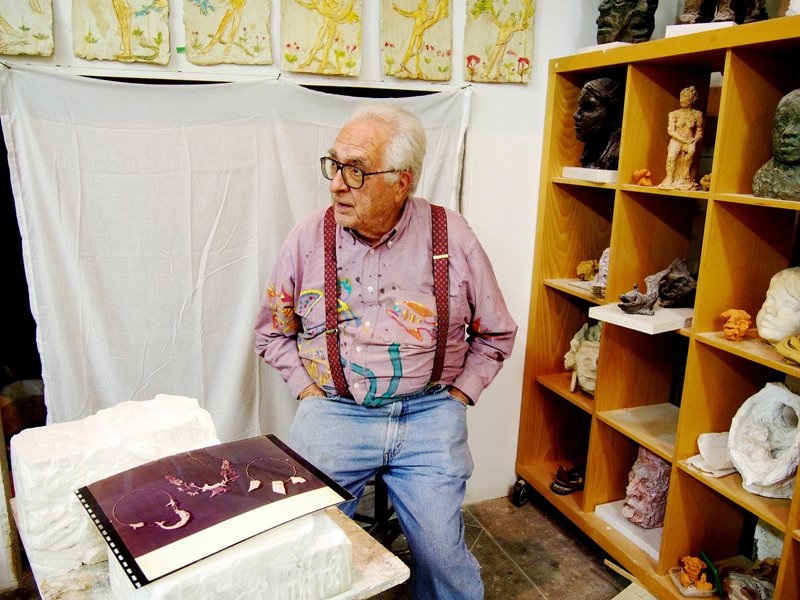

Montebello was with us[2]as we discovered the pieces presented for the 2013 and 2014 editions of Gioielli in Fermento[3]. During these meetings, he revealed his excellent skills of observation, analysis, complicity, and critical investigation, which put the work of each candidate in the context of a world and system of which Montebello is an acute reader and interpreter.

![Gioielli in Fermento 2014, jury session in the studio of GianCarlo Montebello, Milan, with Gigi Mariani, Maria Rosa Franzin, GianCarlo Montebello (photographed), and Eliana Negroni, photo: Eliana Negroni Gioielli in Fermento 2014, jury session in the studio of GianCarlo Montebello, Milan, with Gigi Mariani, Maria Rosa Franzin, GianCarlo Montebello (photographed), and Eliana Negroni, photo: Eliana Negroni]()

![Gioielli in Fermento 2014, jury session in the studio of GianCarlo Montebello, Milan, with Gigi Mariani (photographed), Maria Rosa Franzin, Eliana Negroni, photo: Eliana Negroni Gioielli in Fermento 2014, jury session in the studio of GianCarlo Montebello, Milan, with Gigi Mariani (photographed), Maria Rosa Franzin, Eliana Negroni, photo: Eliana Negroni]()

I met GianCarlo Montebello again in February 2015, and in a rich conversation gathered his ideas and thoughts.

Eliana Negroni: GianCarlo Montebello, your attention to thinking about simplicity is well known. I would like to start by asking you what to expect from the quite exasperating multiplicity of formal approaches that exemplify today’s jewelry. Could this multiplication of “languages” obscure the role and function of a wearable ornament?

GianCarlo Montebello: This multiplicity, this diversity in making, is very interesting because, especially in Italy, it is an expression of the great many ways of interpreting a piece of jewelry, or ornament, as I always refer to it. This is for the most part due to the particularity of Italian geography, which is close to the heart of Europe but stretches into the Mediterranean, until it reaches the shores of North Africa. However, it is clear that alongside variety one should not lose sight of quality. By quality I don’t mean an approved, coded method—because this would not allow for freshness, intuition, and the determination by individual thinking—but a kind of responsibility of thought. Above and beyond multiplicity, we first must find out if before the act of making there is the responsibility of thought. Before any making takes place … it is a good idea to reflect a while.

Do you mean that identifying an individual “language” and some of its interpretative keys has to start with the author?

GianCarlo Montebello: A reflection that starts with ourselves is needed regarding our way of making, our way of working, to join our creativity together with our know-how. What our hands create is worth consideration because the mind is the source. To use a different image: We can define our mind as our software and our hands as our 3D printer capable of translating the most subtle of thoughts.

This means taking time for reflection, knowing how to evaluate intention, and pursuing a consistency in making ... The intention is the cornerstone: the intention guides the project.

Is then your advice to work on identifying a certain path and then evaluating with lucidity all that is superfluous, the noise that can scramble the initial intention?

GianCarlo Montebello: In the face of that exasperating multiplicity you mentioned earlier, the fundamental step of a project is to identify the intention. We must focus on it and develop with determination our ability for self-criticism. This is the point: to develop analytical techno-cultural abilities, with a good dose of severity and strictness toward ourselves, avoiding paths and solutions that are more comfortable and reassuring.

The route is strongly individual, because most of the artists we are talking about are self-employed: We are the only ones who get to review and question our own work during its development phase.

As far as my own experience goes: I think of myself as a designer-craftsman, which implies sharing with others. Taking heed of this need of mine, I decided to pare down projects in order to bring out the method, the project itself, as much as the process of execution and quality—where quality means intelligence and consistency of making.

I am mindful of my original intentions all along the project: The formal result should make manifest not only the feature(s) of the project, but also the skills of those craftsmen and women who translated the design into a physical, material object, using various fabrication processes. This is most important to me. The goal is for an excellent synthesis to come out as the result of sharing and reciprocity between design and execution.

![GianCarlo Montebello, Softness Ellipse, 2009, earrings, 18-karat yellow gold, fire-burnished stainless steel chainmail from the Bradamante collection, 40 x 60 x 1 mm, photo: D. Tettamanzi GianCarlo Montebello, Softness Ellipse, 2009, earrings, 18-karat yellow gold, fire-burnished stainless steel chainmail from the Bradamante collection, 40 x 60 x 1 mm, photo: D. Tettamanzi]()

This working method comes from the experience I have built up since the GEM[4]years, when contact and collaboration between the most highly skilled goldsmith “jewellers” (orafi “gioiellieri”) played a fundamental role in bringing to life pieces of jewelry—or rather ornaments for the body—out from the perfunctory designs of famous contemporary artists. The whole exercise was made possible by participation and exchange based on respective competence.

If I think back over my experience at the European Institute—it was the 1980s, there was talk of training the designer, the stylist, the creative—I remember I insisted on training “designers” (progettisti) capable of bridging the gap between ideas and their realization. Ideas become thoughts to be built and therefore required for a design to go through the practical environment of the workshop.

Now, as then, I believe a creative talent—as an end unto itself—has no reason to exist without the necessary experience in the workshop. Of course it is useful to acquire vision, knowledge, and wealth from the experience of other designers. Nevertheless, the ability to verify one’s own ideas and projects is only possible after working at a goldsmith’s bench, discovering one’s own abilities in manual skills and integrating them to one’s design abilities. This dual preparation is essential in order to have a greater awareness of the feasibility of the project in its entirety, and a deeper knowledge of the materials, the techniques, and their limits.

Your formative vision of the designer was even then a necessity. Many universities abroad today combine theoretical and practical training, but not as many in Italy. Perhaps at present much of the formative aspect is entrusted to the revolution and the spread of rapid 3D prototyping techniques? A method with which everybody can design and create anything, which results in a cold dichotomy: on the one hand, a proliferation of handmade elements resulting from elementary design techniques that are therefore standardized, even banal, and on the other hand, unimaginable and truly virtuoso products resulting from the genius of digital experts ...

GianCarlo Montebello: Exactly. 3D printing is like a wild card: Anyone can do anything. There has been a big pop-style opening up to the technology: Before it was available only to a few within the field of industrial production, and now it is available to all and sundry. I can see the advent of a general and widespread discomfort (in both those who observe, study, and design, and those who look, choose, and wear): “the thinking goes on strike.” This fast-evolving 3D technology may end up being used compulsively as a thing-multiplier to reach consumerist heights never before dreamed of, like slot machines in gaming arcades, and it should come with a warning: Out-of-control use induces addiction and damage.

I would rather the significance of body ornament were not lost, and the quality of the object to be worn were preserved, along with the individual choice of wearing it, of celebrating daily life by choosing a piece of jewelry for oneself.

Today’s rapid 3D prototyping has such an elevated firepower—and a power of saturation … The construction and finishing aspects of fabrication abdicate in favor of fast production, and with them, a main part of the process loses importance. This being the case, it would be interesting to launch an opposite trend, and, say, promote the goldsmith who works on the edge, the jewelry goldsmith.

![GianCarlo Montebello, Retrovisore (Rearview Mirror), 2012, ring, mirror-polished stainless steel trapezium, pure silver band, 18-karat yellow gold stops, 27 x 33 x 33 mm, photo: D. Tettamanzi GianCarlo Montebello, Retrovisore (Rearview Mirror), 2012, ring, mirror-polished stainless steel trapezium, pure silver band, 18-karat yellow gold stops, 27 x 33 x 33 mm, photo: D. Tettamanzi]()

Since the 1870s, and for a large part of the first 40 years of the twentieth century, the definition of jewelry was “the smallest amount of precious metal to hold the largest number of precious stones possible.” This in turn gave rise to refined constructions and surprising mechanisms for the assembly and disassembly of ornaments, in order to satisfy the various requirements of fashion of that time: It is an excellent period to study and research, in order to perhaps rediscover these refined techniques for new contemporary pieces.

Are the economic obligations of our times probably the element that has changed the directions of our sector in such a crucial way?

GianCarlo Montebello: The logic of industrial production and the concept of low cost feed the voracity of consumerist styles, and possibly carry with them devastating consequences from humanitarian and environmental points of view.

If we go back to your reflections about the present reality on the experimental ornament, doesn’t showing, exhibiting, immobilizing pieces in “static” exhibitions risk distancing them from daily use? Isn’t it a paradox to foster public interest in objects “to wear” by erecting pedestals and installations of all kinds? Doesn’t the tendency to show jewelry like sculpture and make it appear like something else de facto put some distance between all that and the human body?

GianCarlo Montebello: I cannot guess how calculated this phenomenon is, or how aware the ones who do this experimental research are, but I would suppose that this oversizing, the out-of-scale-ness in appearance and exhibiting layout, embodies “the variant.” I suppose that the point is to get artworks and their authors to arouse the curiosity of a specific, prime audience: those who choose luxury jewelry. This is when the exhibited jewel can enchant, surprise, and determine status. I am thinking of people who choose high-carat and highly valuable jewelry in the same way that they could choose highly visible and unusual jewelry.

... Of course it is necessary to understand how to exhibit these pieces to attract the attention of people who are used to something else. Being oversized, and overbudget, relates in this case to how contemporary art is proposed and consumed—and this is where we get back to the matter of training and experience.

Everyone can understand instinctively as well as reasonably how to slip into this “other scale.” I recall my own experience in artist’s jewelry, with established artists who thought of the female body wearing jewelry mostly as a moving exhibition space where they could go oversize quite freely. The artist’s jewelry edited by GEM Montebello was designed by painters and sculptors and therefore went to be displayed in galleries: In the period they were made they were shocking—these were the 60s and 70s—they broke with conventions because they transcended the code of jewelry as a status symbol. Today museums and collectors are interested in these very same pieces.

![George Rickey, Hairpins, 1973, earrings and necklace, balancing wires, 18-karat yellow gold, dimensions variable, edition of nine numbered and signed, photo: Antonia Mulas George Rickey, Hairpins, 1973, earrings and necklace, balancing wires, 18-karat yellow gold, dimensions variable, edition of nine numbered and signed, photo: Antonia Mulas]()

![Peter Lobello, PL/1, 1972, earring with folding corners, yellow, white, and rose gold, edition of nine numbered and signed, photo: Antonia Mulas Peter Lobello, PL/1, 1972, earring with folding corners, yellow, white, and rose gold, edition of nine numbered and signed, photo: Antonia Mulas]()

![Peter Lobello, PL/1, 1972, earring with folding corners, yellow, white, and rose gold, edition of nine numbered and signed, photo: Antonia Mulas Peter Lobello, PL/1, 1972, earring with folding corners, yellow, white, and rose gold, edition of nine numbered and signed, photo: Antonia Mulas]()

Does being open to unconventional “languages” and modes of expression mean forgoing, limiting, recoding today’s aesthetic standards?

GianCarlo Montebello: When this happens today we have to call on our awareness, trusting in the sincerity of what we notice and transferring it into our work.

I welcome going beyond conventionality if it demonstrates evolution. However, with regards to experimental jewelry, we have to pay attention to appearances and tags. My work, for example, might seem conventional because I move along the traditional fault line between jewelry and metalwork. We have to develop analytical tools in order to evaluate if a piece shows signs of evolution in its design, and defines a new aesthetic for body decoration.

Sometimes designers’ attention hangs on the necessity of dealing with the physical quality of a piece of jewelry and its powerful front face, while the back must be simply well done. As far as I am concerned, the back side in a piece of work is a consequence of the front side, and this is where quality becomes active, stimulating the project in its multiple aspects of evolution. My bracelet, Double-Face, is an example of this.

![GianCarlo Montebello, Fiches Large, Double Face, 1997, reversible cuff bracelet, 18-karat yellow gold plates, locking white-gold rods and X-shaped stitches, 62 (diameter at top) x 60 mm, photo: BOMontebello GianCarlo Montebello, Fiches Large, Double Face, 1997, reversible cuff bracelet, 18-karat yellow gold plates, locking white-gold rods and X-shaped stitches, 62 (diameter at top) x 60 mm, photo: BOMontebello]()

Lavishness and richness are profoundly different. Lavishness is the quality which includes fine thought, a clear vision of all parts of the project, with an expertise in execution … a paper necklace by a Dutch artist[5]displayed a few years ago at the Triennale (Milan) had these qualities, and was sumptuously regal. Meanwhile, a large set diamond has its stated proven value as an economic status symbol: It is a demonstration of richness, which is not a matter of aesthetics but rather of basic lack of attention… at least in my personal point of view.

Are we still sensitive beyond the aesthetic concept, to shared emotions, to a shared “language,” to harmony playing the main role when designer and observer, creator and end-user meet?

GianCarlo Montebello: The concept of aesthetics as it used to be understood has run its course and has different prospects today: Its definition should move toward a common and shared thought, more ethics than aesthetics. But I feel a certain inattention and a consequential loss in balance, like we said earlier, a basic lack of attention among new generations, distracted by the quick passing over of previous codes, pushed by what I’d call a futuristic technological leap. An example of this is the undifferentiated use of digital tools and 3D printers to which we unwittingly attribute qualities they do not have.

This sensation reminds me of a complete opposite feeling: the awe I felt during my youth in Paris watching a master engraver of ivory spheres and his extraordinary manual skills. They derived from his inner strength and patient dedication, the outcome of which stood as metaphors for a life rich in the experience of skill and know-how.

This could be the key to recoding aesthetics in East-Ethic[6]and rediscovering a balance in the design of future ornaments, conciliating ancient téchne[7]and new technology.

Today, most of the contemporary jewelry works I see are the outcome of mono-techniques, and this kind of approach is very constraining. Yesterday’s goldsmiths used to join various methods, regardless of whether or not they were applied directly by themselves or by their partners, in order to create what had been designed.

Going back to Gioielli in Fermento, it has been interesting to select and arrange the collection and make manifest several ways of seeing and interpreting ornaments today: The way the collection was built reflects an attempt to identify different research areas, and to understand if the authors recognized themselves in all this.

I would also add: with great interest and almost a sense of complicity, in attempting to identify the original and personal touch, discover what’s striking in each piece[8]...

GianCarlo Montebello: Yes, of course, attempting to find that famous intention!

… and to track different research approaches over time, through the work of artists who have participated in different editions of Gioielli in Fermento.

Thank you, GianCarlo Montebello, for the time you have given us.

![Exhibition view, Gioielli in Fermento 2014, Torre Fornello Winery, Ziano Piacentino, Italy, photo: Eliana Negroni Exhibition view, Gioielli in Fermento 2014, Torre Fornello Winery, Ziano Piacentino, Italy, photo: Eliana Negroni]()

![Award ceremony, Gioielli in Fermento 2014, with (from left to right) C. Steiner, N. Frigerio, M. Franzin, L. Pattihis (receiving one of the three awards), G. Mariani, G. Marchesi, G. Milani, M. Nastrucci, E. Negroni, and E. Sgorbati, Torre Fornello Winery, Ziano Piacentino, Italy, photo: A. Petrarelli Award ceremony, Gioielli in Fermento 2014, with (from left to right) C. Steiner, N. Frigerio, M. Franzin, L. Pattihis (receiving one of the three awards), G. Mariani, G. Marchesi, G. Milani, M. Nastrucci, E. Negroni, and E. Sgorbati, Torre Fornello Winery, Ziano Piacentino, Italy, photo: A. Petrarelli]()

ITALIAN VERSION

Conversazione con GianCarlo Montebello

Eliana Negroni

“Cosa è la semplicità? Una complessità non manifesta.”

—GianCarlo Montebello

GianCarlo Montebello è uno tra i pochi orafi al mondo a godere di grande considerazione sia per la propria opera di designer sia per i progetti sviluppati e realizzati per altri autori famosi. Nel 1967, con la sigla GEM, iniziò l’attività di editore di gioielli d’artista: César, Sonia Delaunay, Piero Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hans Richter, Larry Rivers, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jesús Soto, e Alex Katz sono alcuni dei numerosi personaggi con cui ha lavorato. Nel 1978, Montebello iniziò a disegnare e presentare i propri gioielli e in quegli anni partecipò alla costituzione del Dipartimento di Design del gioiello presso lo IED, Istituto Europeo di Design di Milano. Da allora ha realizzato importanti collaborazioni con designers, gallerie e committenze, in particolare in Francia, Stati Uniti e Giappone, e i suoi lavori prendono parte ad innumerevoli esposizioni in tutto il mondo[9].

GianCarlo Montebello[10] ci ha accompagnato nella scoperta dei lavori presentati per l'edizione 2013 e 2014 del concorso Gioielli in Fermento[11]. In occasione di questi incontri, si è rivelato un meccanismo straordinario di osservazione, analisi, complicità, indagine critica che ha messo in relazione il lavoro di ogni candidato a un mondo e un sistema di cui GianCarlo Montebello è acuto lettore e interprete.

Ho incontrato di nuovo GianCarlo Montebello nel febbraio 2015 per raccogliere in una ricca conversazione le sue idee e le sue riflessioni.

Eliana Negroni: GianCarlo Montebello, conoscendo la Sua attenzione a riflettere sulla semplicità, vorrei iniziare chiedendoLe cosa aspettarsi dalla molteplicità quasi esasperata di esperienze tradotte oggi in forma di ornamento contemporaneo. Il moltiplicarsi dei linguaggi potrebbe far perdere di vista il ruolo e la funzione di un ornamento indossabile?

GianCarlo Montebello: Questa molteplicità, questa diversità nel fareè molto interessante, perché esprime specialmente in Italia quella caratteristica intrinseca di manifestarsi in una varietà fatta di molti modi di intendere il gioiello, o l’ornamento, un termine di definizione che preferisco. Ciò è dovuto in massima parte alla particolare geografia italiana, così prossima al centro Europa e protesa nel Mediterraneo fino quasi alla sponda nordafricana. È chiaro tuttavia che accanto alla varietà, non si può prescindere dalla qualità– e per qualità, non intendo una modalità omologata, codificata, perché se così fosse, non ci sarebbe la freschezza, l’intuizione, la determinazione di chi pensa: dunque la responsabilità del pensiero.

Ecco che l'attenzione rivolta alla molteplicità, vuole in primo luogo indagare se a monte del fare, vi sia una responsabilità di pensiero. Prima di ogni fareè bene riflettere.

Quindi una identificazione di linguaggio e di chiave di lettura che deve partire dall’autore?

GianCarlo Montebello: Una riflessione che parta da se stessi, rispetto al proprio fare: il proprio operare, la propria creatività sommata al saper fare. Merita considerazione quanto scaturisce dalle mani perché la mente ne è la sorgente, parafrasando la possiamo definire il nostro software e la mano il mezzo 3D capace di realizzare i pensieri più sottili.

Si tratta di avere un tempo di riflessione, saper valutare l’intenzione, perseguire la correttezza di un fare… L’intenzione è la pietra fondante, l’intenzione guida il progetto.

Il suo consiglio è dunque lavorare individuando un percorso e poi valutare con lucidità tutto il superfluo, il rumore che possa far disperdere l’intenzione di partenza?

GianCarlo Montebello: Di fronte a quella molteplicità esasperata a cui si faceva riferimento, riconoscere l’intenzione, la pietra fondante del progetto, su quella dobbiamo restare e sviluppare con determinazione la qualità dell’autocritica. Questo è il punto: sviluppare capacità di analisi, tecno-culturali, con rigore verso se stessi, evitando di “abbuonare” con percorsi più comodi.

Il percorso è individuale, perché la maggioranza degli autori ai quali mi riferisco si auto-produce: ad ognuno fa capo l’investigare del proprio operato durante l’evolversi del progetto.

Relativamente al mio percorso ho sentito di essere un progettista artigiano, che vuol dire condividere con l’altro: ascoltando questa mia necessità ho deciso di spogliare i progetti per valorizzarne sia la modalità, del progetto stesso, che il processo d’esecuzione e la qualità, qualità intesa come intelligenza e bontà di realizzazione.

Ho sempre curato le intenzioni d’inizio lungo tutto il progetto così che il risultato formale mi fosse manifesto nel duplice intento di rendere visibile la modalità di progetto e, quanto più mi stava a cuore, di mostrare la qualità di chi realizza trasferendo il progetto nella fisicità delle materie e dei differenti processi d’esecuzione di artigiani, donne e uomini, che cercano di lavorare a regola d’arte. Un risultato finale di sintesi ottimale frutto della condivisione e della reciprocità tra progetto e realizzazione.

Questo modo di procedere è frutto della pratica maturata fin dagli anni della GEM[12]in cui è stato fondamentale il ruolo di contatto e collaborazione tra le più alte capacità artigianali - i bravi orafi “gioiellieri”- e dove realizzare i progetti degli artisti nella loro destinazione d’uso di gioiello - o meglio, di ornamento per il corpo - fu impresa di partecipazione e di scambio sulla base delle rispettive elevate qualità.

Ripensando alla mia esperienza all’Istituto Europeo[13]- eravamo negli anni ’80, si parlava di formare il designer, lo stilista, il creativo – ricordo che insistevo perché si formassero dei progettisti capaci di coniugare le idee e la loro fattibilità. Le idee che si fanno pensiero per la realizzazione e da ciò far sorgere la necessità del progetto per poi passare all’esperienza della pratica di laboratorio.

Oggi come allora ritengo che il creativo, fine a se stesso, non ha ragion d’essere senza la necessaria esperienza di laboratorio. Acquisire visioni, conoscenze e ricchezze, dalle esperienze di altri designer, d'accordo, però la “prova del nove” per verificare la validità delle proprie idee e dei progetti è possibile solo dopo un’esperienza al banco orafo: scoprire le proprie capacità manuali da integrare alla capacità di progetto è straordinario.

Fondamentale sperimentare una duplice preparazione per avere una maggiore consapevolezza della fattibilità d’insieme del progetto, la conoscenza dei materiali e l’approfondimento delle tecniche e dei loro limiti.

La Sua visione formativa del designer era già allora una necessità, molti istituti universitari all'estero hanno oggi una rigorosa impostazione in questo senso, in Italia sono pochi, forse oggi molto dell'aspetto formativo è affidato alla rivoluzione e alla diffusione delle tecniche di stampa 3D? Modalità con la quale tutti possono progettare e realizzare tutto derivandone una dicotomia di pari freddezza: una proliferazione di elementi frutto di tecniche di progetto elementari e quindi standardizzate perfino banali, contrapposte a produzioni inimmaginabili, veri virtuosismi frutto della genialità degli esperti di grafica digitale…?

GianCarlo Montebello: Già, la grossa incognita progettuale sul 3D: tutti possono fare tutto, una grande apertura pop di disponibilità tecnologiche prima riservate agli addetti ai lavori individuali o alle produzioni industriali e quanto prima alla portata di tutti indistintamente.

Intravedo un grande disagio (un disagio generalizzato, tanto da parte di chi osserva, studia e progetta, tanto da parte di chi si ritrova ad ammirare e scegliere di indossare), direi: “lo sciopero del pensiero”.

Questo virtuoso strumento 3D se usato in maniera compulsiva come moltiplicatore per il raggiungimento di vette consumistiche mai sperimentate prima, mi fa pensare alle slot machine nelle sale giochi: si dovrà informare che un uso del 3D fuori controllo crea dipendenza e produce danni.

Vorrei non si perdesse il significato di ornamento della persona – la qualità dell’oggetto dedicato al corpo - la scelta di indossare un gioiello, per se stessi, di trattenere un segno che ritualizza il quotidiano.

La prototipazione rapida in 3D, ha oggi una tale potenza di fuoco - e di saturazione - dove gli aspetti costruttivi e le finiture dell’ornamento abdicano per velocizzarne il risultato, e così una parte significativa del progetto cade. Stando così le cose sarebbe interessante innescare la controtendenza e ricercare il maestro orafo che lavora a filo, l'orafo gioielliere. Sin dagli anni settanta dell'800 e poi per buona parte dei primi quarant’anni del '900 per gioielleria, si intendeva il minimo impiego di metallo nobile per trattenere il maggior numero di pietre preziose, e ciò diede luogo a fini costruzioni e sorprendenti meccanismi di scomposizione e di ricomposizione degli ornamenti a soddisfare le varie necessità dell’abbigliamento e delle situazioni: eccellente sarebbe studiare e riscoprire questa tecnica raffinata per nuove opere contemporanee.

Il vincolo economico della nostra epoca, è probabilmente l'elemento che ha spostato in modo determinante le direzioni attuali del nostro settore?

GianCarlo Montebello: Le economie di produzione ed il concetto di low cost, porteranno a conseguenze pesanti sia ambientali che umane, e sempre più svilupperà la voracità degli stili di consumo.

Tornando alle riflessioni sulle realtà attuali dell'ornamento di ricerca, esporre, esibire, immobilizzare le opere in mostre "statiche" non rischia di allontanarle dal requisito di uso quotidiano? E' un paradosso interessare il pubblico a oggetti "da portare" erigendo piedistalli e installazioni di ogni genere per consentirne la fruizione, la tendenza a mostrare sculture che appaiono come altro, di fatto allontanando tutto ciò dal corpo?

GianCarlo Montebello: Non posso valutare quanto di calcolato ci sia, quanta consapevolezza ci sia da parte di chi fa lavoro di sperimentazione: l’ipotesi può essere che l’oversizing, il fuori-scala di forma e relazione espositiva, che tali tendenze nell’ornamento di ricerca incarnino “la variante”, ponendosi l’obiettivo di destare la curiosità di destinatari di fascia alta del gioiello. Ecco che allora il gioiello esibito può affascinare, stupire, determinare status. Destinatari che indifferentemente accedano al gioiello di altissima caratura e preziosità, come al gioiello ad alta visibilità e fuori dagli schemi.

…Certo bisognerebbe capire come esibire queste opere per attirare l’attenzione di chi è abituato ad altro, oversize, overbudget - pensiamo a come oggi l’arte viene proposta e consumata - e qui torniamo a un discorso di formazione ed esperienza.

E' intuitivo, oltre che ragionato, capire come inserirsi in questa “altra scala”, e mi ricollego all’esperienza del gioiello d’artista ad opera di autori ora storici, che pensavano il proprio gioiello per il corpo femminile non come tale, bensì come uno spazio espositivo in movimento: l’artista poteva andare “fuori scala” liberamente. I gioielli d’artista editati dalla GEM Montebello erano di pittori e scultori e giocoforza venivano esposti nelle gallerie, per il tempo in cui sono stati fatti sono stati dirompenti, erano gli anni ’60 e 70 di rottura con le convenzioni d’allora, perché trascendevano la codifica del gioiello come status sociale; oggi quegli stessi pezzi sono d’interesse per i musei e i collezionisti.

Essere aperti a linguaggi ed espressioni non convenzionali significa rinunciare, limitare, ricodificare canoni estetici contemporanei?

GianCarlo Montebello: Per quanto accade oggi, occorre chiamare in causa la propria consapevolezza, confidando nella sincerità di quanto avvertiamo e saperlo trasferire nel nostro lavoro.

Ben venga il superamento del convenzionale se è segno di evoluzione. Tuttavia, riguardo all’aspetto della non convenzionalità nella ricerca, bisogna prestare attenzione alle apparenze e alle etichette: per esempio il mio lavoro potrebbe sembrare convenzionale perché mi muovo nel solco canonico dell’oreficeria e della metallurgia. In questi casi occorre sviluppare un’attenzione e capacità di analisi per valutare se il determinato pezzo reca segni evolutivi di progettazione, che ridefiniscono nuovi percorsi est-etici di decorazione della persona.

Poniamo questo: talvolta l’attenzione si sofferma sulla necessità di affrontare la qualità fisica del gioiello e la sua prestanza di facciata, mentre il retro viene liquidato con un ottimo dal punto di vista tecnico.

Per quanto mi riguarda il retro è la risulta del suo fronte: ecco allora la qualità diventare attiva, stimolare il progetto nei suoi molteplici aspetti di evoluzione. Faccio qui riferimento ad esempio a un mio lavoro, il bracciale Double-Face (vedi foto).

E ancora, profondamente diverse sono la fastosità e la ricchezza. La fastosità è la maestria che comprende finezza di pensiero e visione d’insieme unitamente alla perizia d’esecuzione, un ornamento come il collare di carta - di una artista olandese[14] esposto alcuni anni fa alla Triennale - possedeva questi requisiti di fastosa regalità, al pari un grande diamante incastonato giusto per il suo valore di status socio economico riconosciuto. Si tratta di una manifestazione di ricchezza, non è questione di estetica ma di una intrinseca mancata attenzione, questo è il mio personale punto di vista.

Dunque possiamo essere tuttora sensibili oltre il concetto estetico, a una emozione condivisibile, un linguaggio comune, una sintonia a cui è attribuito il ruolo principale nell’incontro tra designer e osservatore, tra autore e destinatario?

GianCarlo Montebello: Il concetto di estetica come la si intendeva ha fatto il suo corso: oggi il suo divenire è forse l’Est-Etica, più etica che estetica, per un pensiero comune e condivisibile. Constato disattenzione e una conseguente caduta di equilibrio, come detto poco sopra, la mancanza di attenzione, in generale, e che subiscono in particolare le nuove generazioni, tutti distratti dal repentino superamento dei canoni precedenti, sospinti al balzo tecnologico - direi futurista - già presente tra noi. Ne è un esempio l’uso indifferenziato degli strumenti digitali e delle stampanti 3D, ai quali inconsciamente attribuiamo qualità a loro sconosciute

Questa sensazione mi riporta a un sentimento di reazione inversa, l’inquietudine che mi provocava osservando, negli anni giovanili a Parigi, un maestro intagliatore di sfere d’avorio, e le sue straordinarie qualità manuali, dovute alla forza interiore per la necessaria pratica della pazienza con cui vi ci si dedicava: il risultato era nelle sue opere, intese come racconto di uno dei possibili modi di vivere una intera vita immersa nell’esperienza del proprio saper fare.

Qui potrebbe esserci la chiave per superare ostacoli ideologici e ricodificare l’estetica in Est-Etica[15]ritrovando così un equilibrio per ottenere il risultato prefigurato durante la progettazione dei prossimi ornamenti, riconciliando antiche téchne[16] e nuove tecnologie.

Oggi la maggioranza dei prodotti sono frutto di mono-tecniche, questo tipo di approccio è molto vincolante, l’orafo di ieri univa varie esecuzioni, indipendentemente che le applicasse direttamente o che si avvalesse di altri, in un sistema di abilità differentemente dosate per realizzare ciò che si prefissava.

Tornando a Gioielli in Fermento, è stato interessante sistematizzare la collezione e rendere una visione d’insieme sui tanti modi diversi di intendere l’ornamento oggi: anche nel tentativo di identificare aree di ricerca di natura differente, e con il tentativo di capire se gli stessi autori vi si siano riconosciuti.

e aggiungo, con l’interesse e quasi una complicità nel cercare di individuare il tratto personale, scoprire cosa colpisce del singolo lavoro[17]...

GianCarlo Montebello: sì certamente, cercando di intuire la famosa intenzione...!

… e svelare le singole esperienze di ricerca, spesso ritrovare un percorso tracciato nelle edizioni che si susseguono, nel linguaggio individuale degli autori che hanno lavorato in tempi diversi al progetto.

Grazie GianCarlo Montebello, per il tempo che ci ha dedicato.

[1] A detailed biography and whole body of works is available on www.bomontebello.com.

[2] GianCarlo Montebello was a member of the jury of the competition Gioielli in Fermento in the 2013 and 2014 editions. In this interview, he reminisces about that experience and all the activities he was connected with as a member of Associazione Gioiello Contemporaneo (the Italian contemporary jewelry association).

[3]Gioielli in Fermento consists of a competition open to designers and artists resulting in an exhibition of unique jewelry inspired each year by different concepts related to the world of wine. It is hosted at Torre Fornello Winery, in Ziano Piacentino, Italy, which opens its impressive spaces permanently dedicated to a private collection of contemporary art (Vigna delle Arti). The jury, nominated annually, awards the Torre Fornello Award in collaboration with AGC (the Italian jewelry association) and other professional authorities (Joya, Klimt02, ADI Italian Design Association). Curated by Eliana Negroni since its first edition in 2011,

Gioielli in Fermento represents a means of communication about experimentation in action in the world of jewelry.

The Torre Fornello Award today is also a private collection of the most representative artworks from the various editions.

www.gioiellinfermento.com.

[4] GEM Montebello: The Milan precious metal workshop serving artists started by Montebello with Teresa Pomodoro, which operated from 1967 until 1978.

[5] Montebello is referring to the exhibition Gioielli di Carta, curated by Alba Cappellieri and Bianca Cappello and held in Milan at the Triennale Museum in 2009, and specifically to the paper ruff by Nel Linssen.

[6] Montebello plays with the word “aesthetics” and refers to a new “East-ethics” as a way to summon a kind of Eastern sense of discipline, well rendered by that master engraver in Paris.

[7]Téchne, from the Greek τέχνη, “art,” meaning “expertise,” “know-how,” “know how to make.”

[8] During its preliminary meeting, the jury committee of

Gioielli in Fermento begins by giving their first impression of individual works, without knowing who submitted them, before going deeper in the evaluation of all applications. This initial investigation of the artist’s “intention” is always quite involving.

[10] GianCarlo Montebello è stato membro della giuria del concorso Gioielli in Fermento nelle edizioni 2013 e 2014. Ha rilasciato questa intervista riferendosi alle esperienze legate all'attività di AGC associazione gioiello contemporaneo, di cui è membro da vari anni.

[11]Gioielli in Fermentoè un concorso rivolto a designer e artisti orafi che si traduce nell’esposizione di una collezione scelta di opere gioiello uniche ispirate ogni anno a differenti aspetti correlati al mondo del vino. La mostra è ospitata nella tenuta vinicola di Torre Fornello, in Italia, a Ziano Piacentino, che apre i propri suggestivi spazi già animati da una collezione permanente di opere d’arte contemporanea (Vigna delle Arti). La giuria, nominata annualmente, assegna ad ogni edizione il Premio Torre Fornello in collaborazione con AGC Associazione gioiello contemporaneo ed altri enti autorevoli (Joya, Klimt02, ADI Associazione per il Disegno Industriale). Progetto ideato e curato da Eliana Negroni fin dalla prima edizione nel 2011, Gioielli in Fermento rappresenta un modo per comunicare la sperimentazione in atto nel mondo del gioiello.

Il Premio Torre Fornello costituisce oggi anche una collezione privata delle opere più rappresentative delle diverse edizioni di Gioielli in Fermento. www.gioiellinfermento.com

[12] GEM Montebello Il “laboratorio milanese di metallurgia preziosa al servizio degli artisti” avviato da Montebello e Teresa Pomodoro nel 1967 fino al 1978.

[13] Nei primi anni ‘80 Montebello collaborò alla creazione del Dipartimento di Design del gioiello presso l'Istituto Europeo di Design di Milano.

[14] Montebello fa rifermento alla mostra Gioielli di Carta, a cura di Alba Cappellieri e Bianca Cappello che si tenne a Milano in Triennale nel 2009, e in particolare al collare ivi esposto, opera di Nel Linssen.

[15] Montebello crea un gioco di parole tra Estetica ed Est-Etica come richiamo a un approccio ispirato a una sorta di disciplina orientale, ben resa nel racconto dell'episodio del maestro incisore di Parigi.

[16]téchne, dal greco τέχνη, "arte" nel senso di "perizia", "saper fare", "saper operare"

[17] Durante gli incontri della giuria di Gioielli in Fermento, tutte le prime impressioni sui lavori sono state espresse alla cieca, e la ricerca dell'

intenzione è stata molto sentita, spesso era proprio ciò che i membri della giuria osservavano al primo sguardo, durante l'incontro preliminare prima della valutazione più approfondita di tutti i lavori candidati.

![[left] Exhibition view, õhuLoss/Castle in the Air, 2015, foreground work by Tanel Venree form the series Heartology, Evald Okase Muuseum, Haapsalu, Estonia, photo: Villu Plink [right] Kadri Mälk, Stay beside me when darkness rushes through the sluice gates of the night, 2011-15, object, polychrome lilac wood, silver, photo, spinel, L 360 mm, photo: Villu Plink [left] Exhibition view, õhuLoss/Castle in the Air, 2015, foreground work by Tanel Venree form the series Heartology, Evald Okase Muuseum, Haapsalu, Estonia, photo: Villu Plink [right] Kadri Mälk, Stay beside me when darkness rushes through the sluice gates of the night, 2011-15, object, polychrome lilac wood, silver, photo, spinel, L 360 mm, photo: Villu Plink](http://www.artjewelryforum.org/sites/default/files/erev_castle_kkarro_3a_3b_600x800px.jpg)

One of the highlights of the exhibition is definitely Kadri Mälk’s necklace The Finishing Angel, exhibited in Estonia for the first time. The piece seems to have been made exactly for this particular environment. It’s exhibited alone on a wooden board that’s supported by a chair and another board. The fragility of the construction and the mysterious strength of the necklace create a beguiling combination. In the last few years, she’s been working on a new theme—the testament. “I still do as I’ve always done. If something pains me, interests me, I detangle it in my artwork. To see what’s inside. Like cutting open the stomach of a teddybear,” she wrote to me.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is definitely Kadri Mälk’s necklace The Finishing Angel, exhibited in Estonia for the first time. The piece seems to have been made exactly for this particular environment. It’s exhibited alone on a wooden board that’s supported by a chair and another board. The fragility of the construction and the mysterious strength of the necklace create a beguiling combination. In the last few years, she’s been working on a new theme—the testament. “I still do as I’ve always done. If something pains me, interests me, I detangle it in my artwork. To see what’s inside. Like cutting open the stomach of a teddybear,” she wrote to me.![[left] Kristiina Laurits, Red-blooded, 2015, neckpiece, colored curly birch, eggshell, enamel, silver, 300 x 300 mm, photo: Villu Plink [right] Kristiina Laurits, Julius, 2015, brooch, silver, Japanese lacquer, steel, seashell, amethyst, flower, 120 x 30mm, photo: Kadri Karro [left] Kristiina Laurits, Red-blooded, 2015, neckpiece, colored curly birch, eggshell, enamel, silver, 300 x 300 mm, photo: Villu Plink [right] Kristiina Laurits, Julius, 2015, brooch, silver, Japanese lacquer, steel, seashell, amethyst, flower, 120 x 30mm, photo: Kadri Karro](http://www.artjewelryforum.org/sites/default/files/erev_castle_kkarro_7_8_600x800px.jpg)

![[left] Mia wearing a Stardust pin, 2015, selfie [right] Stardust pin glowing in the dark, 2015, selfie [left] Mia wearing a Stardust pin, 2015, selfie [right] Stardust pin glowing in the dark, 2015, selfie](http://www.artjewelryforum.org/sites/default/files/int_miamali_blevine_1_2_600x800px.jpg)

![[left] Monika Brugger, Wound, Gift of the Seamstress, detail, linen, garnets, ± 200 mm, photo © Corinne Janier [right] Monika Brugger, Needle, gold, silk, 40 mm (needle), photo: artist [left] Monika Brugger, Wound, Gift of the Seamstress, detail, linen, garnets, ± 200 mm, photo © Corinne Janier [right] Monika Brugger, Needle, gold, silk, 40 mm (needle), photo: artist](http://www.artjewelryforum.org/sites/default/files/aint_monica_brugger_4_5_600x800px.jpg) What were you thinking about as you put together the work in Damage Control?

What were you thinking about as you put together the work in Damage Control?![[left] Monika Brugger, Fingerhut, ring, gold, silver, 20 mm diameter, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris [right] Monika Brugger, A Thimble!, earrings, aluminum, red gold, garnets, ± 50 mm, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris [left] Monika Brugger, Fingerhut, ring, gold, silver, 20 mm diameter, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris [right] Monika Brugger, A Thimble!, earrings, aluminum, red gold, garnets, ± 50 mm, photo: Corinne Janier, Paris](http://www.artjewelryforum.org/sites/default/files/aint_monica_brugger_14_15_600x800px.jpg)

What interests you about absence?

What interests you about absence? Monika Brugger: Everything has to do with coincidence. I was invited to the artist-in-residence in Bienne and didn’t bring all my tools with me. At the same time, I was occupied by the question of the interaction between brooches and garments and thinking about the relationship between the object and its support. A brooch can’t exist without the clothes. So it was possible to explore my interest about the result of “a thing” on the body and not about the “thing.” My intention was not to provide a decorative object designed to be placed on clothes but to set out to contaminate fabric with shapes and patterns. It provided an association so that the final piece could be considered a sculpture, a jewel, or a dress. I tried to make the brooch as abstract as possible, revealing its associated functions as a vehicle for personal identity, underlining social and ritual roles while questioning society as a whole. It could depict a body-borne stigmata, corporatist markings, private signs, or work-induced scars.

Monika Brugger: Everything has to do with coincidence. I was invited to the artist-in-residence in Bienne and didn’t bring all my tools with me. At the same time, I was occupied by the question of the interaction between brooches and garments and thinking about the relationship between the object and its support. A brooch can’t exist without the clothes. So it was possible to explore my interest about the result of “a thing” on the body and not about the “thing.” My intention was not to provide a decorative object designed to be placed on clothes but to set out to contaminate fabric with shapes and patterns. It provided an association so that the final piece could be considered a sculpture, a jewel, or a dress. I tried to make the brooch as abstract as possible, revealing its associated functions as a vehicle for personal identity, underlining social and ritual roles while questioning society as a whole. It could depict a body-borne stigmata, corporatist markings, private signs, or work-induced scars. Monika Brugger: It is never the material I’m interested in; it is the concept of the project that determines the materialization of my ideas. I’m inspired by stories and images like the photograph by Dorothea Lange called Mended Stockings, from 1934, or the novel

Monika Brugger: It is never the material I’m interested in; it is the concept of the project that determines the materialization of my ideas. I’m inspired by stories and images like the photograph by Dorothea Lange called Mended Stockings, from 1934, or the novel  I learned sewing in school, I make my own wardrobe, I like fabrics and the feeling they provoke. I use clothing because it speaks about the whole. It has movement, a silhouette, and a reference to the human as a whole. Jewels are the details. They need a place to exist. They have this extraordinary quality “to assist” or to perfect the beauty, the attractiveness, and perhaps the illusions that wearers and makers want to create. I’m always attracted by images depicting “la couture” or the representation of female archetypes and other tricks to make someone look beautiful. But it is the project that gives me the opportunity to explore uncommon and common materials.

I learned sewing in school, I make my own wardrobe, I like fabrics and the feeling they provoke. I use clothing because it speaks about the whole. It has movement, a silhouette, and a reference to the human as a whole. Jewels are the details. They need a place to exist. They have this extraordinary quality “to assist” or to perfect the beauty, the attractiveness, and perhaps the illusions that wearers and makers want to create. I’m always attracted by images depicting “la couture” or the representation of female archetypes and other tricks to make someone look beautiful. But it is the project that gives me the opportunity to explore uncommon and common materials. I think that it is also necessary to understand my work in a French context. There was not really a contemporary jewelry movement when I started in the 90s. Jewelry was identified by the “haute joaillerie” or the fashion jewelry/custom jewelry industry. We had few schools, and less support from the national institutions or museums. So in a way France was a kind of “no man’s land.” This gave me the possibility of exploring different approaches and the possibility to find answers to the questions in a proper way. I know that it was this environment that gave me the right atmosphere to explore, to progress, to make, to ask questions, and that introduced this kind of approach, which is connected with the fashion industry, “la mode” and the vision of femininity in France.

I think that it is also necessary to understand my work in a French context. There was not really a contemporary jewelry movement when I started in the 90s. Jewelry was identified by the “haute joaillerie” or the fashion jewelry/custom jewelry industry. We had few schools, and less support from the national institutions or museums. So in a way France was a kind of “no man’s land.” This gave me the possibility of exploring different approaches and the possibility to find answers to the questions in a proper way. I know that it was this environment that gave me the right atmosphere to explore, to progress, to make, to ask questions, and that introduced this kind of approach, which is connected with the fashion industry, “la mode” and the vision of femininity in France.

Likewise, Yuka Oyama’s enormous paper animal heads (mythical and otherwise; one 2010 dragon is titled Metamorphic Spirit), which in her words represented “expanded concepts of jewelry,” though delightful and a highlight of the show, provided less of a jewelry experience than an opportunity for highly theatrical cross-species transformation. Oyama is a trained jeweler whose website, tellingly, does not have a “jewelry” category and who is perhaps better known for

Likewise, Yuka Oyama’s enormous paper animal heads (mythical and otherwise; one 2010 dragon is titled Metamorphic Spirit), which in her words represented “expanded concepts of jewelry,” though delightful and a highlight of the show, provided less of a jewelry experience than an opportunity for highly theatrical cross-species transformation. Oyama is a trained jeweler whose website, tellingly, does not have a “jewelry” category and who is perhaps better known for

This led me to another website in which Pietzsch wrote that Ogawa’s project would pursue “likenesses of jewelry that exist only momentarily through the diffusion and fragmentation of light.”

This led me to another website in which Pietzsch wrote that Ogawa’s project would pursue “likenesses of jewelry that exist only momentarily through the diffusion and fragmentation of light.”

Left to themselves, show-goers may have found aspects of the exhibition provocative, yes, but also off-putting. The problem was that they were there mainly as passive viewers of the projects, many of which required further explication to be fully understood and/or evaluated—hence my extensive Googling. And there was something counterintuitive about presenting participatory art in what amounted to a textbook setting. Had After Wearing been presented entirely online as an interactive work of art in itself, the show might have gained in effectiveness. I mean, once you dump the jewelry, why not dump the venue as well? Here was a show that assumed a “post-studio” posture only to embrace the gallery. By relocating post-gallery, i.e. online, After Wearing would have opened its virtual doors to a far greater audience invited to share its responses to the show’s unstated yet strongly implied question: What exactly is contemporary “jewelry,” and does relocating “typical discussion” of it “within a context of participation and use”

Left to themselves, show-goers may have found aspects of the exhibition provocative, yes, but also off-putting. The problem was that they were there mainly as passive viewers of the projects, many of which required further explication to be fully understood and/or evaluated—hence my extensive Googling. And there was something counterintuitive about presenting participatory art in what amounted to a textbook setting. Had After Wearing been presented entirely online as an interactive work of art in itself, the show might have gained in effectiveness. I mean, once you dump the jewelry, why not dump the venue as well? Here was a show that assumed a “post-studio” posture only to embrace the gallery. By relocating post-gallery, i.e. online, After Wearing would have opened its virtual doors to a far greater audience invited to share its responses to the show’s unstated yet strongly implied question: What exactly is contemporary “jewelry,” and does relocating “typical discussion” of it “within a context of participation and use”

Eileen Townsend: Can you tell me about your background, both your early life growing up in Latvia and your career since you graduated from the Art Academy of Latvia?

Eileen Townsend: Can you tell me about your background, both your early life growing up in Latvia and your career since you graduated from the Art Academy of Latvia?